(In this post I summarize a research paper I recently presented at the Philosophy of Computer Games conference. I tried to leave out as much academic jargon and complexity as possible, while keeping the main points of the text. The original paper can be found here)

“Hi, my name is Link and I am a Hylian. I am also known as “The Hero of Time”. This is because I am the chosen one who explores the virtual world of the Zelda game series as a protagonist, while pursuing an important quest for justice and peace.

I am also a vegan.

This does not only mean that I refuse to eat animal products. In fact, I try to avoid all aspects of speciesism that I encounter during my adventures. I don’t kill or bully other creatures, I don’t buy any leather or wool clothing items, I don’t pick up weapons made of bones, and I don’t tame or ride horses. On the other hand, I eat a lot of veggies and I do my best to fight the evil spirit of Ganon.”

Michel Foucault (1926-1984) was a French philosopher that focused his work on notions of power, freedom, and knowledge. Particularly in his later work, he emphasized the active and critical negotiation we can have with power structures as well as practicing different ways of living with limitations. He aimed to reframe our understanding of concepts like power and freedom not as static limitations but as arbitrary constraints that can be negotiated with and that give us the possibility to continuously reshape ourselves.

The methods and practices that could be used for styling or transforming one’s self were defined by Foucault as ‘technologies of the self’ (Foucault, 1988, p. 18). He hoped that freedom could be obtained through the practice of ‘care for the self’: to give a certain shape or style to one’s own life as a form of ethical or aesthetical self-fashioning (Foucault, 1988). In this context, self-fashioning refers to the constant and life-long practice of exerting power over one’s own life in order to find a personal sense of freedom. This is done by taking the liberty to impose rules and disciplines over our own lives that shape specific ways of living freely within existing structures of domination and oppression.

By playing The Legend of Zelda – Breath of the Wild. (BOTW) (Nintendo, 2017) through a vegan-run I tried to practice Foucauldian self-fashioning with my-self (both virtual and actual) through disruption and destabilization of the default gameplay. This type of adjusted playing style is also called ‘expansive gameplay‘. Similar to speed-runs or pacifist-runs, but with a clear focus on improvised decision making that is based on a guiding set of broadly interpretable values.

Veganism is understood here as a general and interpretable ideology, not a strict set of rules. So instead of a predefined set-out challenge (such as “don’t kill anyone” (in the case of pacifist-runs) or “complete the game as fast as possible” (in the case of speed-runs)) the game is approached according to values that can be negotiated with. Questions that come up while playing characterize the vegan movement at large and include things like ‘what is considered a living creature?’, ‘when is hurting another creature as a form of self-defense appropriate?’, ‘what should I do if I receive an item that contains animal products as a gift?’. In other words, it requires a constant exploration and willingness to reinvent what it means to be vegan.

In my daily life, it is often very difficult to avoid animal consumption entirely (I might not be fully aware of the ingredients of certain types of food, there might be no adequate vegan options available, or I need to take into account the socio-cultural dimensions of being offered food as somebody’s guest). However, in the world of BOTW, those decisions can be made much more rigidly. In other words, now I am the protagonist in my own game and I establish veganism as the new standard to live by. Something that is largely impossible in the actual world where veganism is considered to be far outside of the norm and I am often ridiculed or demanded to explain myself.

As feminist theorist Margaret A. McLaren wrote, critical practices such as self-writing and autobiography are empowering and political forms of liberating self-care – Foucauldian technologies of the self – specifically for marginalized individuals (2002). I argue that engaging with decision making in fictional worlds (such as by playing videogames or writing fan-fiction) might add an intense dimension to self-fashioning that provides an empowering safe-space of negotiating political decisions that are perhaps impossible to negotiate with in real life.

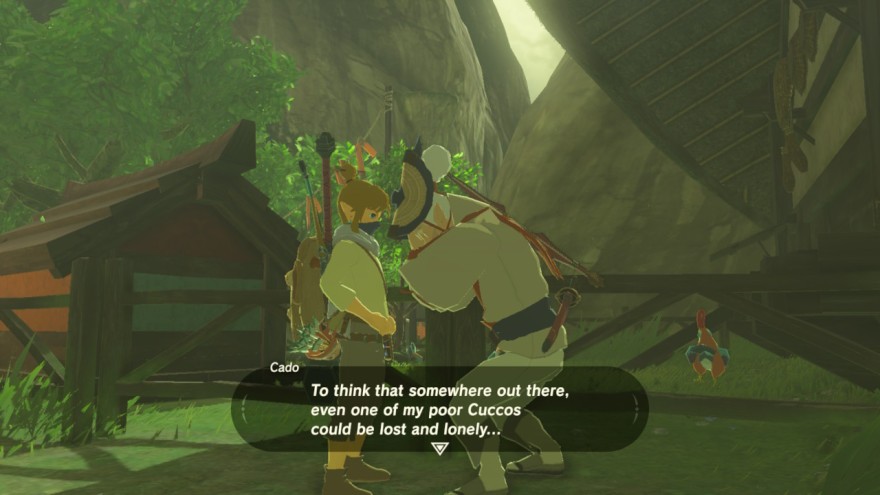

“In the morning, I head out to explore Kakariko town. I try to talk to some of the inhabitants about speciesism, but they all seem busy or uninterested. Then I pass by a small chicken farm. An older man with a tall hat and a white beard is standing in front of the fence. He is covering his face with both hands. He seems upset. I decide to approach him.

“Hey, what’s wrong?”, I ask.

“My precious Cuccos. They escaped! What do I doooo… AAAARRRRGH!! Please, help me find them and put them back behind the fence”, he says, gasping for air in between words.

“Your chickens escaped? How?” I reply.

“THEY MADE A HOLE IN THE FENCE. I already covered it up again. But 10 of them are gone.”

“Hmm, interesting”, is all I can come up with for now, and I walk away.

I find several of the escaped chickens roam around the village that day, picking up grains from the ground and sleeping peacefully on top of the signposts. Later, when it gets dark, I head back over to the farm. It seems like nobody is around. Quietly, I climb over the fence, carefully pick up each of the chickens that remained in the enclosure and release them in the field behind the farm. This feels so good. I finally feel like I accomplished something.

I sleep wonderfully that night.”

A few other games scholars have written about the notion of Foucauldian self-fashioning in virtual worlds as well. But mostly from a general perspective. For example, they argued that playing and designing virtual worlds are transformational activities that allow for changes in terms of social criticism, training and teaching, ethics, interpersonal relationships, creative thinking, and philosophical inquiry (Gualeni, 2014). Or they are skeptical about the effectiveness or productiveness of games functioning as practices of self-fashioning, because virtual worlds are too different from real life (Parker, 2011).

However, I think that my specific experience of playing BOTW as a vegan could offer something to this discussion. I found that, rather than a small-scale simulation of real life, the gameplay offered me an extra imaginary space that shapes my relation to power in real life. A space where a vegan utopia or a firm political response towards certain vegan ideologies can be imagined, materialized, strategized, and played out. Is this form of virtual self-fashioning then only an illusion or small-scale playground because it takes place inside a world of fiction? Or can those empowering virtual spaces instead offer the effectiveness and productiveness that are needed to reimagine and negotiate power, but are not (yet) available or granted to those that need it in real life?

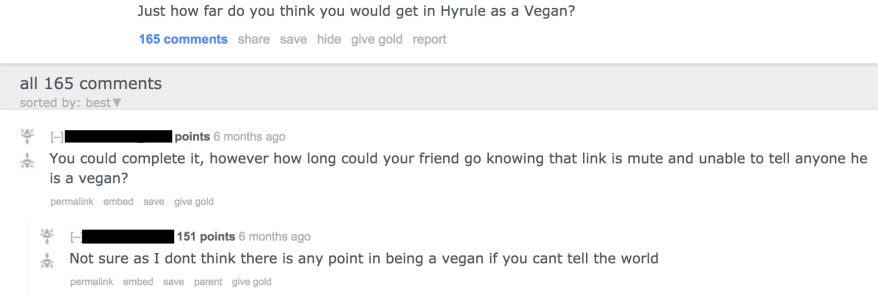

I think that the following online discussions of other people’s experience with their vegan-run of BOTW exemplifies that these fictional forms of self-fashioning do impact our perspectives in the real world.

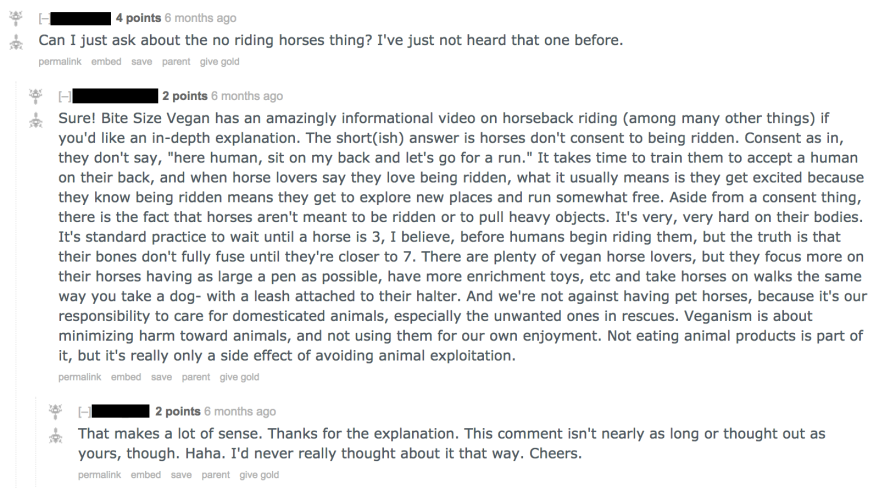

Even though the BOTW vegan-run discussions seem much more ad-hoc and tentative, they open up a certain kind of unstructured and non-authoritarian space in which players discuss their experiences and perspectives. Discussing vegan-run experiences and strategies led to different conversations on the topic of what veganism entails and how this form of playing relates to our interactions with animals in real life.

These conversations help to situate one’s own vegan practices in relation to other people (both vegan and non-vegan). Furthermore, I argue that they could even function as a nuanced form of animal activism by promoting and detailing a vegan agenda that is emerged within the fictional or hypothetical context of the game, but also includes concepts that extend into the real world. But above anything, these forms of playing and discussing give vegans a space for self-individualization and exploration that is not usually granted to vegans in society. Suddenly, regular BOTW players want to know the details of my in-game diet, why I avoid horse riding, how I managed to accomplish specific quests, and whether I consider mechanical monsters as sentient or not.

Conclusions

In this paper, I set out to extend the discussion within the game studies community on the topic of Foucauldian self-fashioning with a focus on a specific kind of expansive gameplay (a vegan-run) in a specific game (BOTW). I argue that further inquiry into different forms of self-fashioning (such as playing with and within virtual worlds and generating new narratives from those worlds) constitutes an important step towards social and political transformation. More specifically, I aimed to show how the practice of expansive gameplay and sharing those experiences with others could be regarded as self-fashioning tools and offer both empowerment and political action to marginalized individuals.

Nonetheless, we should remain critical towards assigning too much political importance to these playful practices and continue to evaluate how they fit into existing power structures and potential resistance to those. What happens to an individual that receives hateful comments after sharing her experiences? Do fictional spaces that resemble safe zones for marginalized people risk becoming addictive forms of escapism? What is the role of the technologies themselves that are involved with this self-fashioning and transformation (such as the game or online medium that largely determines how (inter)actions are shaped)?

To investigate these questions within the field of practically engaged philosophy, I suggest that there is much knowledge to be gained from looking at individual experiences, procedures, and techniques of the self (rather than solely focusing on universal statements or general theory).

Please feel free to share your thoughts in the comments-section below.

References

Foucault, M. (1988). Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. Edited by Martin L. H., Gutman, H. and Hutton P. H. London, UK: Tavistock Publications.

Gualeni, S. (2014). Freer than we think: Game design as a liberation practice. POCG 2014, retrieved here.

McLaren, M. A. (2002). Feminism, Foucault, and Embodied Subjectivity. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Nintendo (2017). The Legend of Zelda – Breath of the Wild. Nintendo Switch (screenshots taken by the author).

Parker, F. (2011). In the domain of optional rules: Foucault’s aesthetic self-fashioning and expansive gameplay. POCG 2011, retrieved here.